Marcos Chin Illustrates the Sensual Art of Longing

Marcos Chin doesn’t draw people so much as summon them - whole worlds of them, limbs entwined, eyes half-lidded, calves that curve like questions. His figures stretch across page and screen like they’re mid-sonnet, posed in reverie or disco or divine contradiction. One hand in the clouds, one holding a purse. Sometimes both.

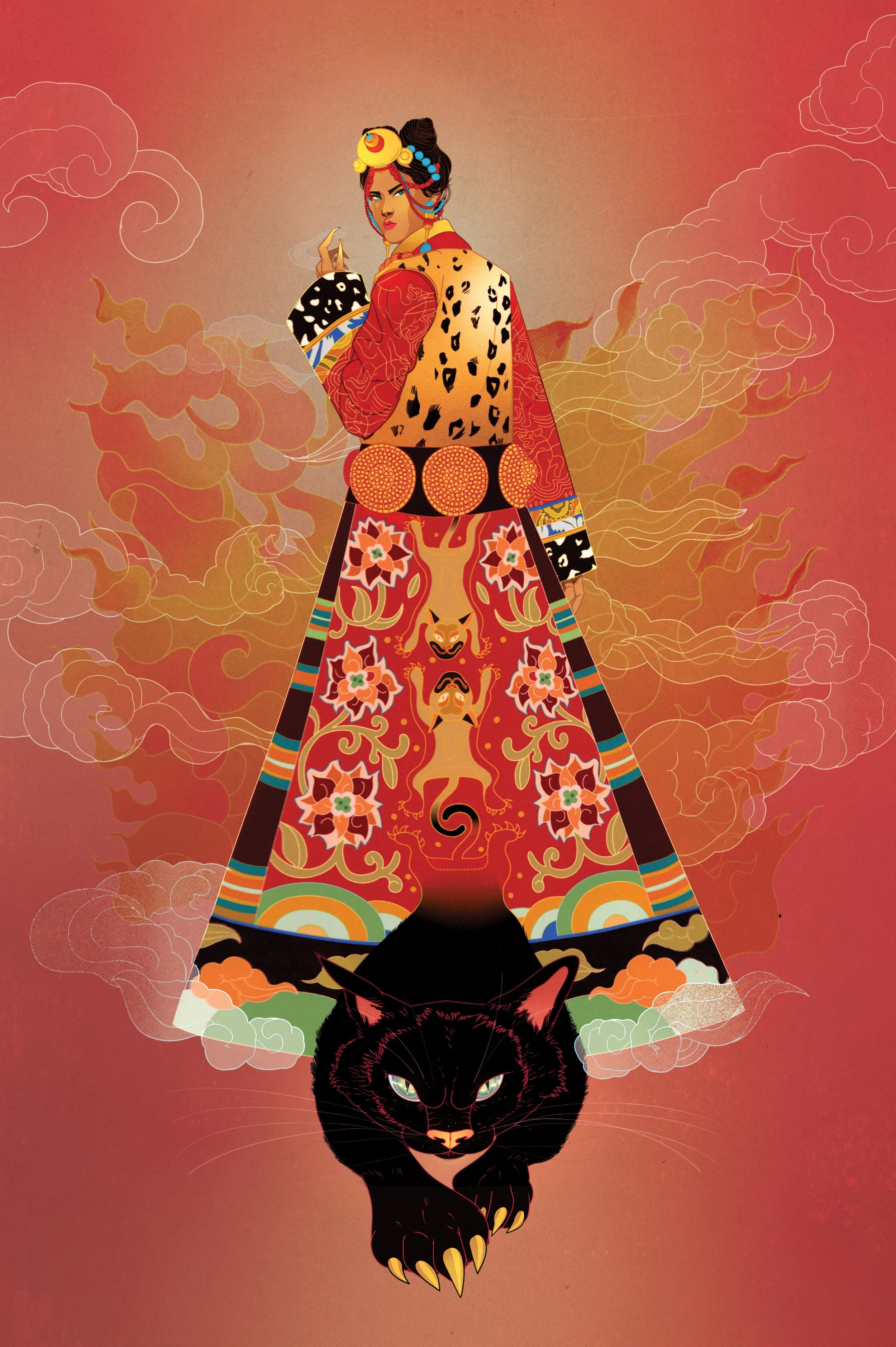

A Toronto native now based in Brooklyn, Marcos is best known for his lush editorial work, fashion illustration, and elaborate surface designs, where bold figures melt into rich tapestry: tattoos, vines, haloes of hair and fabric, all coiled in graphic ecstasy. His linework sings with confidence, even when his subjects look like they’re daydreaming through a fog of heartbreak, heat, or hypnotic synthpop. This is an artist obsessed with beauty. But not the boring kind. Not the beige influencer kind. Marcos’s beauty is queer, floral, gently muscular, and defiantly soft. It stares back. It sways. It flirts with your assumptions and gives them a better haircut.

His collaborations range from The New Yorker to fashion brands and book covers, and yet there’s always something deeply Marcos in the work: an intimacy of gesture, a celebration of touch, of decoration as identity. Whether he’s painting male nudes wrapped in vines or illustrating a Vogue-ready dreamscape, there’s never a wasted shape, never an unconsidered line. As a teacher at the School of Visual Arts, Marcos is also shaping the next wave of illustrators with the same clarity and tenderness that runs through his work. He’s open about the need for queer visibility in commercial art: not as an aesthetic trend but as a lived, layered truth.

What Marcos Chin offers isn’t just illustration: it’s a sensual cartography of modern identity, mapped in ink and emotion. He draws the world the way we wish it looked when we closed our eyes: a little more fabulous, a little more vulnerable, and unapologetically adorned. And really, how often does a single image make you want to slow dance, get a tattoo, and call your therapist?

The Archive on the Walls

“I devoured comics, cartoons, and storybooks as a kid,” Marcos says. “Old Master Q from Hong Kong. I couldn’t read Chinese, but the characters held my attention.” His father clipped newspaper images and movie posters, storing them alongside his children’s drawings. “Maybe staring at those every day became part of my visual DNA. We also had a bunch of Asian god calendars taped onto the walls of our home for good luck,” he adds. “It was just normal. But looking back, I think those textures and symbols embedded themselves into me visually, even if I didn’t consciously realize it.”

From Mozambique to the MTA

After leaving Mozambique due to civil war, Marcos’s family arrived in Canada with almost nothing. “My dad couldn’t find steady work. He was angry and stressed. That broke my self-esteem.” So when Lavalife called - originally a small NYC campaign - it felt surreal. “It exploded. Suddenly, my illustrations were everywhere: the subway, cities across North America. It changed everything. It was one of the biggest inflection points in my life,. Clients saw I could carry a big campaign. It was the most money I had ever seen. I bought a computer instead of renting one. A desk. A chair. A bed. Before that, I was working on the floor with my monitor stacked on cardboard boxes. I didn’t grow up imagining this kind of success. I didn’t know how. I had a very small opinion of who I believed I was.”

Identity Arrives Later

Though Marcos had worked with queer publications, queerness wasn’t central to his art until 2017. “I felt very little responsibility to express my queerness through illustration. That changed when the world changed: MeToo, Black Lives Matter, LGBTQ+ rallies outside my front door, Covid, anti-Asian violence. A new question appeared: Why am I making this work? It gave my work a soul. Purpose beyond money or success. I realized I wanted people to see parts of themselves in my drawings.” He came out in his mid-twenties but had been advised not to include queer content in his portfolio. “Back then, being gay meant you were a token side character - a jester. Asians were mostly invisible, or caricatured. Emasculated, feminized, fetishized. Queer Asians? Forget it. So the decision to show up fully as myself in my work - queer, Asian, vulnerable - felt radical. But necessary.”

The Classroom and the Mirror

At the School of Visual Arts, where Marcos has taught for nearly 19 years, his approach is collaborative. “I see my students as individuals and encourage them to co-create the course with me. I share my own vulnerabilities, life experiences, the mistakes and lessons too.” He’s big on repetition and reflection. “We make, we talk, we revise. Sometimes I’ll assign writing prompts to get students thinking about their beliefs, their motivations. It’s like an anthropological study of oneself. Illustration is a connector. It lives in the world. It activates when it’s seen. It can be a platform for social commentary. That means knowing what you’re trying to say and saying it with clarity.”

Pleasure, Fashion, and the Kama Sutra

When asked to illustrate the Kama Sutra, Marcos wanted to avoid clichés. “I didn’t want it to feel dirty or lascivious. I’m not ashamed of sex or nudity, but we needed something tasteful - intimate but not explicit. A lot of the original text was about the natural world. So I began with flora and fauna.” He was also nervous. “At first I hesitated drawing a heterosexual couple having sex. But then I realized, it’s not about gender. If I focused on emotional and physical connection, the rest would follow.” His love of fashion runs parallel. “Before I studied illustration, I wanted to be a fashion designer. Later, I took night classes in sewing, patternmaking, draping. I even studied Shibori, twisting and dyeing fabric to create patterns. Fashion has always been part of my visual storytelling, the way bodies are adorned, layered, made symbolic.”

Scale and Sculpture

Public art brought new challenges. “It forced me to wear new hats: project manager, team leader, producer. I had to think about scale, durability, materials. Things I never considered as an illustrator.” In one nine-month collaboration, Marcos helped create a large metal sculpture with a team of ten. “I had no experience in metalsmithing. But we checked in regularly, trusted each other’s skills, and made something that exceeded expectations. Public work is different. It doesn’t need to grab attention in three seconds like a billboard. It can breathe. It can reveal itself slowly.”

Representation, Reality, and the Long Game

“Diversity matters and things have changed. Now I’m sometimes hired because I’m gay or Asian or both. That never used to happen. But the industry still lags. It’s tied to corporations, shareholders, politics. I’ve had clients say ‘don’t include that’ because they’re scared of backlash. We’re not there yet. But the arc is bending in the right direction.”

Metaphor, Message, and What Lasts

Every illustration starts with a core idea: a few words, a sentence. “Then I build visuals around that. I use metaphor, simile, mystery. I try to make the image poetic.” Commercially, he knows how to share authorship. “When I work for clients, I adjust. It’s their story too. It becomes a shared voice. But when I make personal work, that’s all mine. That’s when I don’t compromise.”

Final Advice for the Ones Still Coming Up

“Make work you care about. Make a body of work, not just a few nice pieces. Be prolific. Be consistent. Confidence is built through action. Through mistakes and recovery. Treat it like work, not a hobby. Show up. Even when no one’s watching or paying. Especially then. And when the jobs come? Be kind. Kindness sustains a career. Do good work. Deliver on time. Build trust. That’s what gets you hired again.” And yes: “Pay your taxes.”